Don't Get Duped by Fake Degrees: Diploma Mills Going Strong

Millions of fake degrees are in circulation but only a fraction, like the 7,600 U.S. nursing degrees, have been exposed. And now, the key measure in combating them, accreditation, is under threat.

Just a couple weeks ago, 7,600 nursing degrees were exposed as fraudulent. The owner of the diploma mill, the alleged “Palm Beach School of Nursing”, Johanah Napoleon, was charged $3.5 million and sentenced to over a year and a half in prison. Nurses from Texas to New Jersey have been removed in what is dubbed “Operation Nightingale”.

Yet, fake degrees are nothing new. Over 40 years ago, George Arnstein wrote:

“Diploma mills have long been a festering sore on the academic landscape.” - G. Arnstein, 1982

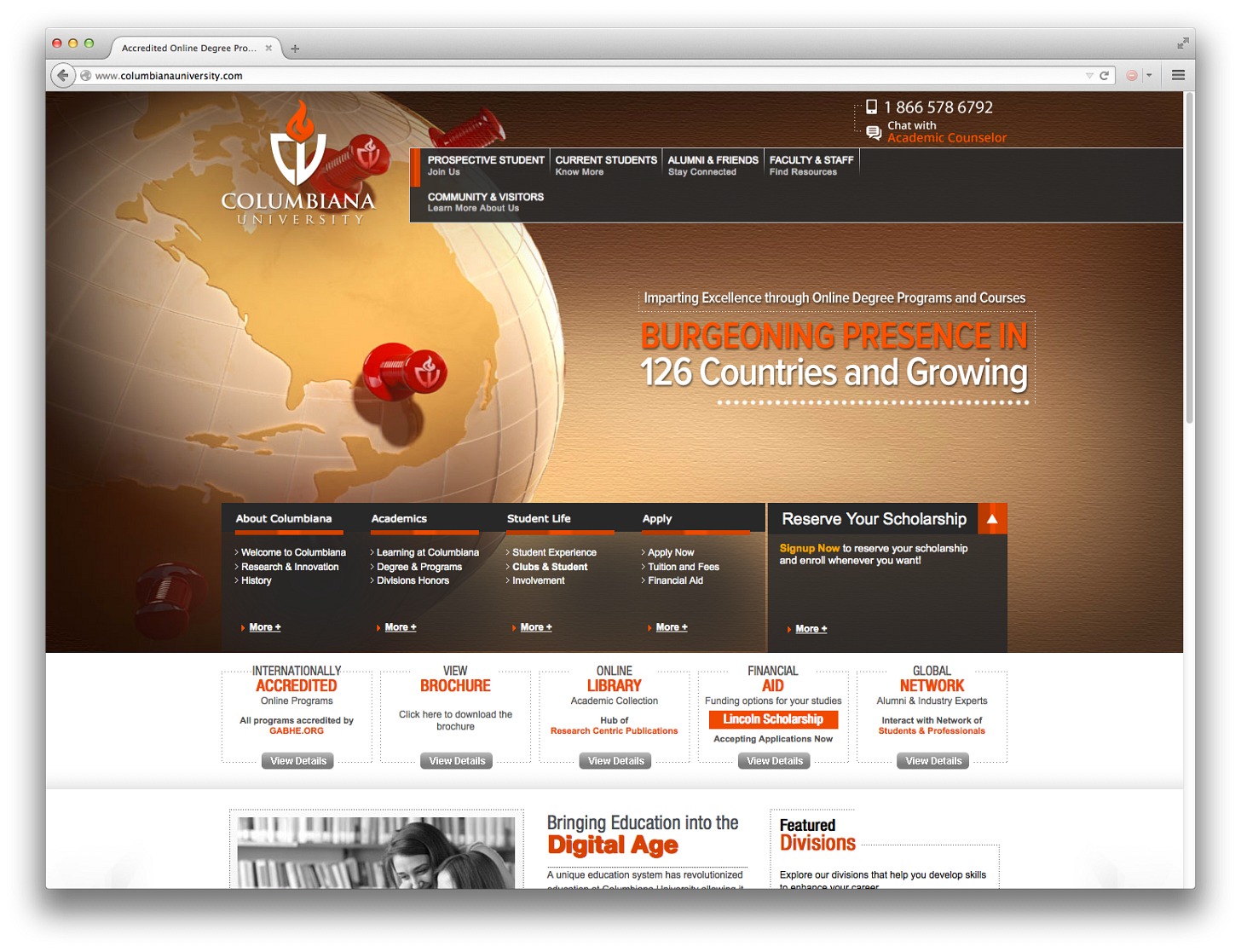

Like many issues in academia, all is quiet until a new scandal breaks out and circulates. In 2017, over 40 websites pushing fake degrees for real British universities were shut down. In 2008, 350 U.S. government employees with fake degrees were discovered after a 3-year investigation that unearthed over 120 fake universities. Yet, all these pale in comparison to one of the biggest exposures, the 2015 Axact case. This Pakistan-headquartered establishment awarded 2.2 million fraudulent degrees from its dozens of high schools and almost 100 universities — all backed up by its 16 fake accrediting bodies. The subterfuge operated for about 20 years and had 370 fake websites at its peak.

Diploma mills are a complex, multi-layered issue which extend well beyond academia, and even beyond employers, going into the spheres of politics and educational reform. In this newsletter we’ll dive into how these degree mills arise, why accreditation is key to controlling them, and how current education reform may be compromising our best solution to the problem.

What are diploma mills?

Diploma mills, simply put, are illegal organisations selling counterfeit degrees. The degrees themselves are generally from non-existing institutions, but sometimes are fake degrees from real universities. Although the majority of consumers likely purposefully purchase these diplomas, their motivations vary. The main market diploma mills target are people seeking diplomas in order to enhance their professional standing. However, the “fake degree” business isn’t as black-and-white as it first appears. As higher education costs become ever more unaffordable, employers’ demands for specific certificate and degrees become harder to fairly meet.

For example, in the case of the recent nursing degree scandal, many of the customers were legitimate licensed practical nurses (LPNs) who wanted to become registered nurses. Registered nurses (RN) make significantly more money than LPNs, but to transfer from LPN to RN is expensive, and usually takes 200-500 clinical hours. Thus, paying $17,000 on a RN diploma to immediately increase their income was much more appealing than waiting 2-4 years (and even greater costs) to complete the new training.

Alternatively, in the Axact case, pushy salespeople would often manipulate consumers who were seeking genuine education, or convince them that they needed special certificates. One tactic involved impersonating U.S. officials and threatening customers that their degrees would be worthless if they didn’t purchase State Department authentication certificates. The customers were clearly ignorant that these certificates were directly available from the U.S. government for less than $100, whereas Axact would charge thousands for each.

How to combat fake degrees?

Diploma mills have been around for a while — a long while. Educators were already wary of them over a century ago:

“[Diploma mills are] a scandal and disgrace to American education.” - John Eaton, 1876, U.S. Commissioner of Education

Why are diploma mills still around then? Like with other issues in academic integrity, the motivating factors behind the malpractice plays a key role. The extreme costs of higher education, particularly in the U.S., and employers’ focus on diplomas both fuel the diploma mill industry. Plus, dissolving diploma mills is a lengthy legal process. Even today, prominent Axact diploma holders are still being caught, almost a decade after the universities were exposed.

When it comes to cracking down on fake degrees, the responsibility rests largely on the shoulders of employers — those creating a demand for the degrees in the first place. Organisations need to adopt careful due diligence in verifying diploma authenticity, and can do so by relying on external screening parties. A great example of this is South Africa’s commercial background screening company, which operates in over 30 African countries.

However, employers can’t know the details of every institution, nor can they universally afford expensive, global screening processes. What matters here is not only if an institution is real, but what value their degree-holders have. This question was resolved as early as the 1940s when a new requirement entered higher education: accreditation. Accreditation single-handedly ensures the quality of an institution’s education, but, as we’ll see, is now facing its own battles.

Accreditation: the greatest weapon against fake degrees

Accreditation is a formal system by which the quality of higher education can be evaluated and upheld to certain standards. In the 1940s, when the GI Bill was passed, the U.S. government required that higher education institutions meet certain standards verified by accreditation organisations.

Today, many countries verify the quality of their higher education institutions either by government councils or accrediting bodies. In Greece, for example, there is one recognised body and its accreditation is compulsory for all universities. In Germany, there are 10 certified agencies. The U.S. has dozens of institutional accreditors. But, in order for an institution to receive financial aid and take federally-funded students, it must be accredited by an organisation that the US Department of Education recognises.

Not only is accreditation the best line of defence when it comes to diploma mills, but it furthermore defines how academia responds to changing times. For example, accreditation plays a major role in:

Preventing government censorship (educational gag orders)

Protecting tenure

Promoting DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives)

Although accreditation is our best bet, it’s not impervious to abuse. As soon as accreditation requirements entered the arena, accreditation mills popped up. That’s why the Axact case had 16 fake accreditation organisations behind it. So, when determining the validity of a diploma, it’s as important to verify the accrediting body as it is to check if the institution itself is real.

Threats to accreditation are threats to free speech

The political and cultural debates in the U.S. are increasingly entering the academic arena, putting accreditation at risk. Last month, The Heritage Foundation (a conservative think-tank in the U.S.) demanded that Congress “dismantle the higher education accreditation cartel”. They argue universities should be able to take students on federally-funded financial aid, even if they are not officially accredited (current laws do not allow this).

But threats to accreditation are no longer just theoretical. Florida, for example, has fought against accreditation for years. Last year, a law was passed requiring universities to change accrediting agencies every two years, which was an obvious play in the culture wars against accreditors. Last month, Governor Ron DeSantis sued the federal government over the Higher Education Act, in an attempt to completely dissolve the requirement of accreditation for federal funding.

Why is this a threat to free speech? Andrew Gothard, the President of the United Faculties of Florida, a union representing professors across all Florida universities, provides a succinct answer:

“…Governor DeSantis wants to have unilateral authority to control what does and does not get taught in higher education classrooms across Florida. One of the most significant barriers to the kind of authoritarian control is higher education accreditation.” - Andrew Gothard

What happens next in the U.S. cultural wars of higher education, gag orders, and accreditation requirements for federal funding remains to be seen. But no matter how the politics shake out, it’s clearly in the best interest of employers and institutions to recognise and rely on accreditation as a key factor in evaluating the quality of degrees.

Found a suspect diploma? Check if the institution is on any list of known degree mills (U.S., India, Pakistan, or Wikipedia’s list of unaccredited institutions). You can also verify with that country’s degree verification system or publicly available databases (like UK’s HEDD or the European EQAR database). If you think you’ve found a fake university, follow-up by reporting to the appropriate authorities, like the Better Business Bureau or Federal Trade Commission in the U.S.

Resources

Accreditation Can Support Diversity Efforts in the Wake of the Supreme Court Decision, July 2023

Ex-owner of South Florida school tied to fake nursing diploma racket will serve 21 months, July 2023

University of Southern California sued over online 'diploma mill' programs, May 2023

A fake ‘Massachusetts Central University’ has resurfaced online. Here’s what to know. April 2023

How Thousands Of Nurses Got Licensed With Fake Degrees, Feb 2023

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: A Tour of Axact, the “World’s Largest Diploma Mill”, Jan 2023

Fake university degree websites shut down, 2017

Diploma Mill Concerns Extend Beyond Fraud, 2008

An Introduction to the Economics of Fake Degrees, 2008

Credentialism: Why We Have Diploma Mills, 1982

Degree Mills: An Old Problem & A New Threat, Council for Higher Education Accreditation

European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education (EQAR)

92 Things Bad And Fake Schools Do To Mislead People

This article is a powerful wake-up call. Fake degrees don’t just hurt employers—they undermine trust in education and put real lives at risk, especially in fields like nursing. Accreditation is essential, yet it’s under political attack. We need stronger protections, smarter verification, and more public awareness. Thank you for shedding light on this hidden crisis. https://medium.com/@SterlingPhoenix/the-dangers-and-consequences-of-buying-fake-diplomas-or-degree-transcripts-online-1ccf79568555