How the Best Scientists Avoid Burnout

Burnout is an epidemic among graduate students and researchers globally. But, there's a lot to learn from how the most notable scientists in history coped with heavy workloads and high pressure.

Although burnout is one of the most hackneyed and widely-discussed issues pervading academia and professionals globally, it doesn’t seem to be improving. Even with the myriad of self-help books and resources available, the epidemic continues to affect millions of students and employees.

If you’re burned out, you may feel:

“I am achieving less than I should.”

“Run down and drained of physical or emotional energy.”

“There is more work to do than I practically have the ability to do.”

However, burnout isn’t a necessary side-effect of success. Some of the most notable scientists in history succeeded by working not just hard, but smart. By balancing personal interests, hobbies and external outlets with their work, they enabled the most ground-breaking contributions, while supporting their mental health.

In this issue of The Scoop, we’ll examine how notable scientific figures like Richard Feynman and Barbara McClintock wove their personal and professional lives together, for the betterment of their lives and craft. Their commitment to both science and personal wellness hold valuable and perhaps surprising lessons for researchers today.

What is burnout?

Burnout refers to being over-worked to the point of feeling drained, hopeless, and even resentful. Herbert Freudenberger was one of the first psychologists to study burnout, and his 1974 paper on the subject has over 15,000 citations today. No field is immune to the phenomenon. Whether in a factory or university, any one can experience the symptoms and negative health consequences of burnout.

The very term “burnout” is perhaps part of the problem. It implies we are like engines running out of fuel or lightbulbs left on too long — inanimate objects expected to operate efficiently, no matter personal circumstances.

Today, plenty of resources help diagnose and relieve burnout. You can find recommendations on everything from staying hydrated to doing hobbies. However, a combination of systematic issues, culture, and individual limitations still leaves many people stuck in this cycle of over-work.

Burnout lessons from great scientists

Many of the most successful researchers and scientific contributors in history managed to flourish despite long hours and difficult circumstances. Most seemed to pursue a range of interests and hobbies, which evidently gave their lives balance and fueled their scientific careers. Here are some of their stories, and what we can learn from them.

Feynman: From bombs to bongos

Richard Feynman, one of the greatest physicists of all time, struggled with burnout after working intensely on the Manhattan project. Over the course of a few years in the 1940s, Feynman worked laboriously alongside other physicists on the first atomic weapons. He was so immersed in his work that even when his wife passed away, he spent only a few days off before going right back to work to witness the famous Trinity nuclear test.

After the project, Feynman was burned out. To cope with this, “he would go to the library and sit there for hours reading Arabian nights.” Feynman also found joy in drumming. After working on the bomb, he went on to work at Cornell where he discovered his interest in percussive instruments. He even took part in musicals and productions in the Drama Department.

Takeaway → Explore hobbies like reading, music and performance.

McClintock: Walking to new ideas

Barbara McClintock’s contributions to genetics led her to win the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Even today, she remains the only woman in history to have received an unshared prize in that field. In the 1940s and 50s she identified DNA sequences known as “jumping genes”, or transposable elements (TE), which move from one location on the genome to another. Over the decades, scientists realized TEs were present in nearly all organisms, and make up about half of the human genome, and 90% of maize genome which McClintock originally studied.

During this creative period of her life, McClintock enjoyed walking on the grounds of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory where she worked. According to her biography, “Rain or shine, from at least the early 1950s through the 1980s, alone or with a friend, she hiked through the woods... Out in nature but near the lab, these walks led to a string of minor discoveries that sparked her synthesis of the races of maize and controlling elements. On these walks, she integrated heredity, development, and evolution.”

Takeaway → Take some long walks to think and talk.

Schrödinger: Renaissance man

Erwin Schrödinger was best-known for his contributions to theoretical physics, particularly to the wave theory of matter and quantum mechanics. His 1926 paper introduced a novel, probabilistic model of the atom, and laid the foundation for much future work in the area of quantum mechanics (Schrödinger's equation).

What really set Schrödinger apart though was his remarkable curiosity and enthusiasm for a range of disciplines. In addition to physics, he “felt at home” in philosophy, literature, and even ancient Indian writings. He enjoyed German poetry, evidenced by quotations from poets like Goethe in his philosophical book “My View of the World”.

This “renaissance man/renaissance woman” attitude is certainly not limited to Schrödinger, and many contemporary researchers manage to exemplify this value. Dr. John Ioannidis, a well-known researcher in the field of meta-science, is also known for his published literary work in Greek and interest in poetry.

Takeaway → Indulge in your curiosity of different subjects.

Carl Sagan: Facts and fiction

Carl Sagan, one of the best known astronomers of the last century, had a remarkable career both within and outside of academia. In addition to his scientific success, he offered advice to NASA and the Apollo crew before journeys to the moon, helped define humanity’s presence via the Voyager Golden Records, and authored over a dozen science books geared towards inspiring the general public. Sagan’s attitude of adopting a range of projects serves as an excellent example of public speaker Alexander Den Heijer’s belief: “You often feel tired, not because you've done too much, but because you've done too little of what sparks a light in you.”

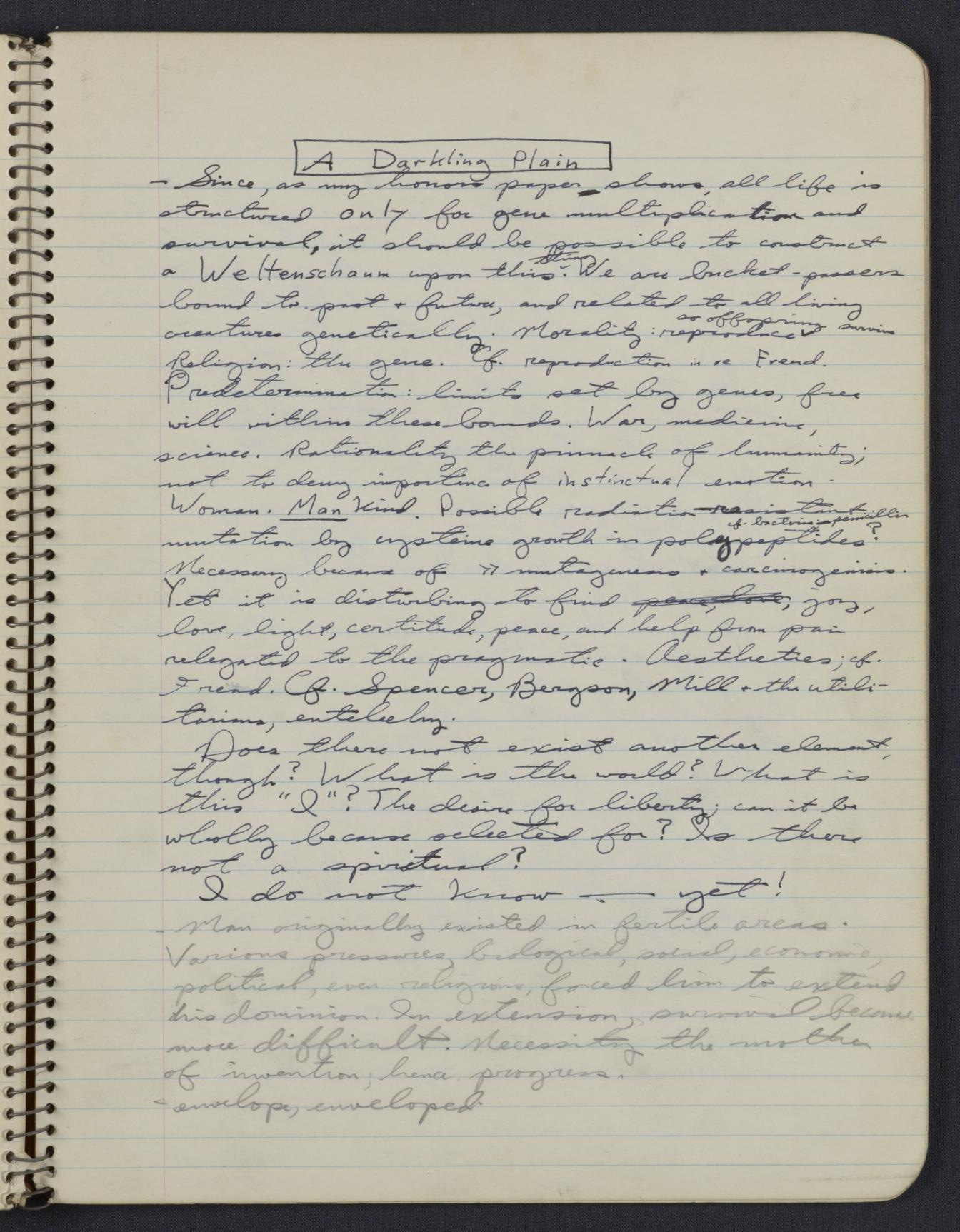

Even with such an ambitious career, Sagan also found time to relax. He spent time with his family (collaborating even professionally with his wife), wrote fiction (Contact), and explored many ideas beyond astronomy (see his notes below).

Takeaway → Diversify your projects; indulge in your curiosity of different subjects.

Rosalind Franklin: Summiting for success

Rosalind Franklin studied DNA in the 1950s, before anyone understood the structure or chemical makeup of DNA. It was her DNA photograph, taken using X-ray diffraction, that helped set James Watson and Francis Crick on the right trajectory to develop the double helix model. Franklin ended up writing a supportive paper to Watson and Crick’s model, without ever knowing how her photograph helped the two with their discovery. In addition to her photographic contribution, Franklin also published over a dozen papers on the molecular structure of viruses, all in her brief 10-year career.

Franklin was a fan of physical activity and the outdoors. She was an avid hiker and traveler, spending weekends hiking with friends from her laboratory and vacations walking and cycling. She would travel and hike throughout Europe, and was captivated by French culture, evidenced by her mastery of the French language and cuisine.

Takeaway → Enjoy the outdoors, exercise, and travel.

Although the most successful scientists in history no doubt worked incredibly hard, they managed to also balance their personal and work lives effectively, ensuring the sustainability of their productivity. It can be tempting to equate hours worked with value, but most contemporary productivity guidance tends to discourage this mindset. As Feynman, McClintock, Schrödinger, Sagan and Franklin all show, successful scientific careers aren’t just compatible with fulfilling personal lives, they are fueled by it.

How do you deal with burnout?

Share your thoughts below to help your peers and colleagues balance their work-life better, for better research and scientific success.

Avoid burnout by tackling your research efficiently.

Use Litmaps to accelerate your literature review. Join our upcoming webinar to learn how.

Resources

The Busy Professor by Dr. Timothy Slater

Burnout to Brilliance by Jess Stuart

Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

The Burnout Society by Byung-Chul Han

Are We Living in a Burnout Society?, April 2024

How Burnout Became Normal — and How to Push Back Against It, April 2024